A radical approach

“The exercise of imagination is dangerous to those who profit from the way things are because it has the power to show that the way things are is not permanent, not universal, not necessary.”

A controversial history

Hypnosis has attracted controversy since the very beginning, when Franz Anton Mesmer became renowned for throwing women into fits in perfumed rooms in Paris in the late 1700s - scandalous behaviour that led to an investigation by his former patron Louis XVI. Thousands of case studies of beneficial results were ignored, it was deemed to be complete humbug and a report was issued describing mesmerism as a threat to public morality. Mesmer was ‘exposed’ by a fraud squad and fled Paris in disgrace. Mesmerists risked being expelled from respectable societies.

There may have been something in the accusations: hypnosis is indeed disruptive, as is any pathway into trance. In trance we freeze the narrative, which gives us time to view the cycle of trigger and reaction from outside while also providing a degree of internal calm that makes us less susceptible to manipulation.

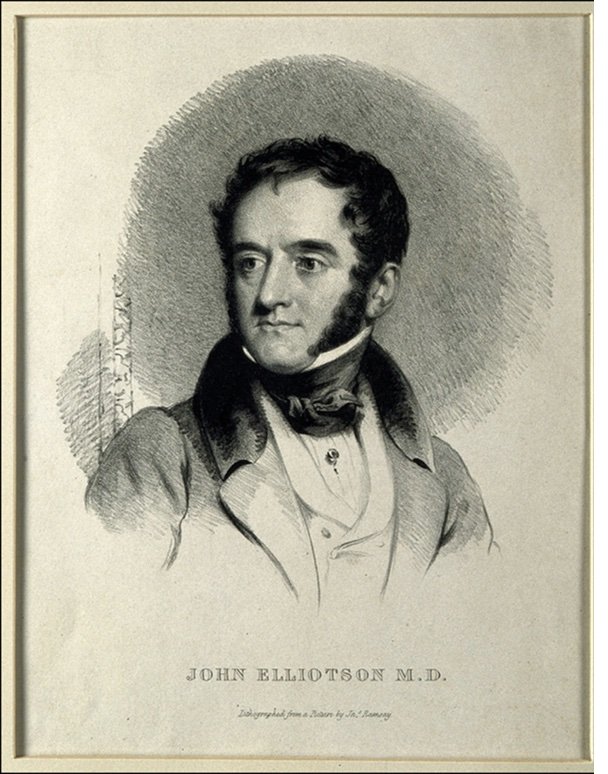

Mesmerism flirted with respectability again the following century when Professor John Elliotson - the man who pioneered the stethoscope in England - reported miraculous results for all types of conditions. In 1837, amidst a wave of hype, he staged a demonstration of his star subject Elizabeth Oakey at University College Hospital, where she wowed the great and the good of London’s Victorian medical establishment by going into full-body catalepsy and allowing the doctor to push pins into her without flinching. But she also shocked the assembled by pointing at the trousers of the audience, even laughing at their trousers in a manner most unbecoming of a young working-class woman of the era. For her finale she refused to come out of trance at the gentleman’s command, insisting that his assistant bring her out of trance. Hierarchies were publicly upended; to the medical journals it was an outrage.

Mesmeric anaesthesia

Elliotson soldiered on, presenting an account in 1843 of an amputation under mesmeric trance to the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society, of which he had once been president. The gentlemen were not impressed by ‘the strokings and clawings of the necromancer’, and concluded that the ‘poor ignorant peasant’ patient simply ‘betrayed no sensation of agony’ as saw passed through bone.“ They will not try their mountebank tricks again before the profession,” concluded the report.

Elliotson was relieved of his academic posts, but his correspondent Dr. James Esdaile went on to oversee over a thousand mesmeric operations at his Calcutta hospital; the medical community concluded that weak-minded Hindus had been tricked into not flinching when an arm, cataract or penis was removed. 19th-century surgeons normally required strong men to subdue the amputee for an operation, and mortality rates approached 50%, compared to only 5% in Esdaile’s hospitals. When ether anaesthesia was discovered later in the decade, it was welcomed as a weapon not against pain so much as against mesmerism. Unlike trance, which can be induced by anyone with patience and a voice, anaesthetic requires complex equipment and access to drugs, and keeps the control of pain under the control of the profession. Although mesmeric surgery and dentistry occasionally appear in the popular press, the medical press rarely reports on this promising technique, which is a testament to the skilful political machinations of physicians of the mid-1800s.

Quaking, shaking and breaking convention

If trance can change something so intimate as how we perceive our bodies, it can also change how we view the body politic. Indeed, the reason I’m so dedicated to it is that I believe that trance work can change not only your life but all our lives by breaking our collective trance in this dark historical moment of disenfranchisement and disenchantment.

The morality matrix we grow up in is what Freud called the superego; in my culture it harbours the idea that success is measured in terms of how much cash you receive rather than how much love you give, and it includes such collective monstrosities of thought as patriarchy and unreconstructed class dynamics. When the superiority of the superego is undermined much becomes possible, and it can happen with a simple reframe. I was in a zoom meeting once at a previous job, watching myself and everyone else bend over backwards to accommodate the whims and objections of someone who did very little work and couldn’t be persuaded to do the basic reading that would answer her objections. I texted a colleague, asking her to imagine the words being uttered in a scouse accent rather than in her posh one, and the curtain fell; we had found someone to replace him within the month.

Liberation through contemplation

Disruptive trance predates hypnosis. In the 16th century, Teresa of Ávila and John of the Cross, the author of Dark Night of the Soul, emphasized the importance of solitude and contemplation, and Martin Luther spent so much time in contemplation that his superior ordered him to do more work. All three were key drivers of reform movements. The late 17th century Quietists followed a similar practice and came to similarly radical conclusions, and were condemned by Pope Innocent XI. By then the Reformation had released Christians in various European countries from the dogmas and power structures of the Roman Catholic church, but many were not satisfied by the new order. The Quakers decided they would only say what was true in their meetings, and gradually said less and less until they were saying nothing in their meetings except occasionally when someone felt moved by the Holy Spirit. They emerged from their worshipful silences to pioneer some of history’s greatest campaigns against the government, refusing to pay war takes and engaging in naked acts of civil disobedience.

The same types of practices are found at the root of some of the great radical movements of the twentieth century driven by people with deep contemplative practices, regardless of their creeds. The renuncient Gandhi rallied India against the Raj, Minister Martin Luther King raised a movement against segregation in the USA and Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc self-immolated in South Vietnam in 1963, which brought down the government he opposed. William Godwin, who renounced Christianity, wrote that “truth dwells in contemplation” and “can scarcely be acquired in crowded halls and amidst noisy debates.” Today he is considered to be the founder of philosophical anarchism.

Perhaps the disruptive behaviour of those drawn to techniques of trance is the reason that the God-struck were often whisked away to monasteries up mountains, out of sight and out of mind, far away from any right-thinking folk they might corrupt with their heavenly infinities. In Europe they swore solemn vows before the Eternal Father to remain at the monastery, in poverty, to be obedient and well-mannered - in some traditions they took a vow of total silence. A merchant looking for something sublime might climb the mountain to pray before the Lord and His serene and taciturn friars, before heading back down to town to salute the Crown and the officers of the watch.

Staying open-minded

The Medical Health Act of 1858 divided the medical marketplace, placing on one side traditional practitioners such as herbalists, bone-setters and female midwives, and on the other those trained in what would become state medicine. Approved medics were placed on a list of sanctioned practitioners - when a negligent doctor is “struck off the list” today, that’s the list we’re talking about.

Medicine became sanitized, and has become more so ever since. In this environment, hypnotists sought respectability by distancing themselves from Mesmer and leaving behind their murky roots entwined with the Spiritualist movement and various radical programs of political reform. Schools of hypnosis often teach a rather formulaic approach today, and some practitioners can be a little cold and clinical in their approach.

For my part, I am open to the magic of the unconscious, and I’ve seen too many weird and wonderful things in my life and in my practice to say anything definitive about how the mind and the world interact. When I’m with a client I follow the trance where it leads. I was surprised once when the journey crossed a wheatfield and into a story about finding a crystal hanging in a tree there, but I was even more surprised when we came out of the trance to be told that my client had indeed found a crystal pendant hanging from a tree in a wheatfield in real life. My supervisor’s comment was simply that telepathy was part of the job.

I have some ideas about what it all means or what is possible, but that is the nature of the conscious mind; my job is to keep my mind open and allow miracles to happen where they will. For example, I don’t tend to go into past-life regressions (I can’t remember what I had for lunch yesterday, so it seems optimistic for me to remember how I commanded French troops at the Battle of Rivoli). That said, in sessions pinpointing trauma along the timeline, a client does occasionally scan back through adolescence and childhood, all the way back to the womb and indeed beyond. This has happened organically a few times, and when it does the story that has emerged from a previous life has provided a key to resolving an issue in this life.

It is not for me, nor for any conscious observer, to muzzle the unconscious when it is producing material that heals and inspires creativity. Maybe it is all in the mind. But maybe Mind is larger, more porous and more powerful than it is usually given credit for.

Let’s see what we can do with it.